by Veronica Gaitán

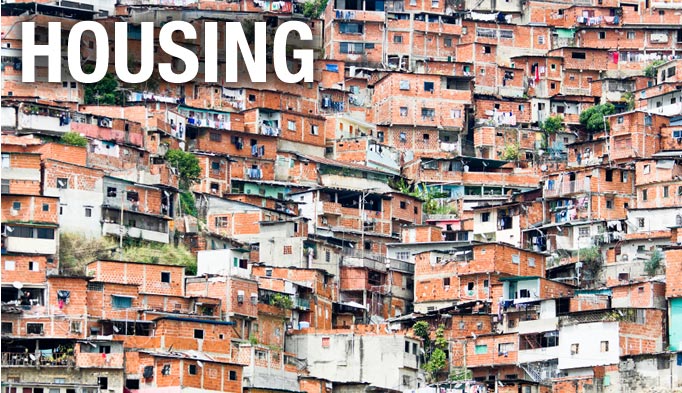

Many social issues stem from a history of unstable, unaffordable, and poor-quality housing. Research shows that housing is the first rung on the ladder to economic opportunity for individuals and that a person’s access to opportunity is intrinsically linked with that of the community at large. As the gap between rents and incomes widens, it is critical that professionals in fields outside housing—including health, education, and economic development, among others—understand its central importance.

The following research shows how housing can create better educational opportunities for children, contribute to healthier people and neighborhoods, and build stronger economic foundations for families and communities.

How housing affects educational outcomes

Children who live in a crowded household at any time before age 19 are less likely to graduate from high school and tend to have lower educational attainment at age 25.

Living in poor-quality housing and disadvantaged neighborhoods is associated with lower kindergarten readiness scores.

Homeless students are less likely to demonstrate proficiency in academic subjects. Passing rates for English language arts, math, and science exams are lower among homeless students than among their housed counterparts.

For typical households in the Fremont Unified School District, the impact of school quality on housing prices is more than three times greater than the impact found in studies in other regions. This impact matches the cost of private education for a child, suggesting that home prices act as tuition for in-demand public schools.

Near a high-scoring public school, housing costs 2.4 times as much, or roughly $11,000 more a year, as housing near a low-scoring public school.

In one study in New York City, improvements in a school’s test scores are associated with higher home values and increased spending on residential investments (whether by owners or developers). Improving a school’s scores by one standard deviation was correlated with a 1.8 percent increase in housing values.

Housing and financial instability often lead to children moving to poorer schools.

How housing affects health outcomes compared with New York City residents who stay in gentrifying neighborhoods, displaced residents who move to nongentrifying, low-income neighborhoods have significantly higher rates of emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and mental health–related visits for about five years after displacement.

Being behind on rent, moving multiple times, and experiencing homelessness are associated with adverse health outcomes for caregivers and children and with material hardship.

Households with poor housing quality had 50 percent higher odds of an asthma-related emergency department visit in the past year.

People with mental illness or an intellectual or developmental disability are less likely to receive responses to inquiries about rental housing and less likely to be invited to inspect available units.

Renter households with children are more likely to have asthma triggers in their homes than owners. They are also more likely to have at least one child with asthma.

In a study of single-parent families living in violent neighborhoods, parents met or exceeded the national average for self-reported physical health but fell below the mental health average. Forty percent reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression and reported higher levels of stress from worrying about financial instability and concern for their children’s well-being.

In one study, older homeless adults who obtained housing during the study reported fewer depressive symptoms than those who were still homeless at follow-up.

How housing affects economic outcomes

Black per capita income is lower in regions with higher levels of economic and black-white segregation.

There is a positive relationship between high levels of automobile ownership and estimated rates of foreclosure and mortgage default, suggesting that transportation costs affect housing affordability.

In Detroit, strong efforts by residents, coupled with support from community development organizations and external assistance, led to increased neighborhood housing prices in middle- and working-class neighborhoods that lost value in the foreclosure crisis. Residents’ efforts were less effective in higher-poverty neighborhoods with lower rates of owner occupancy.

The need for access to good jobs in central locations that is driving the lack of affordable housing shows that access to housing and access to opportunity are inextricably linked, which affects future intergenerational mobility.

Places with higher job accessibility by public transit are more likely to attract low-income households that do not own cars but have at least one employed worker, demonstrating that job accessibility by transit affects housing location choice.

Economically healthy cities tend to have higher rankings on economic, racial, and overall inclusion than distressed cities.

Federal housing assistance—from housing vouchers, to welfare-to-work programs, to financial coaching and incentives, and more—improves lives. Housing policies can be a tool to fight poverty and create upward mobility, making assistance a worthwhile and imperative investment in America’s future.

Photo by Anastasios71/Shutterstock